The pioneering fashion imagery of Paolo Roversi

A new monograph on the Italian photographer traces the evolution of his experimental practice, which has constantly pushed the boundaries of fashion photography

“There are photographs that have the potential to exist outside of a magazine; in a book, a museum, a gallery … and others that die after they are published in the magazine,” Paolo Roversi says in an interview that appears in his new monograph.

Only a few pages in it becomes clear why his substantial body of fashion photographs, many of which were made for magazines, belong to the former category – and not just by virtue of the fact that his images have indeed appeared in books, museums and galleries.

The book has been edited by curator Sylvie Lécallier in close collaboration with Roversi, the product of a nearly ten-year process that is traced in a diaristic timeline in the book. Lécallier oversees the photography collection at Palais Galliera in Paris, where an exhibition took place last summer, marking the museum’s first solo show on a living photographer.

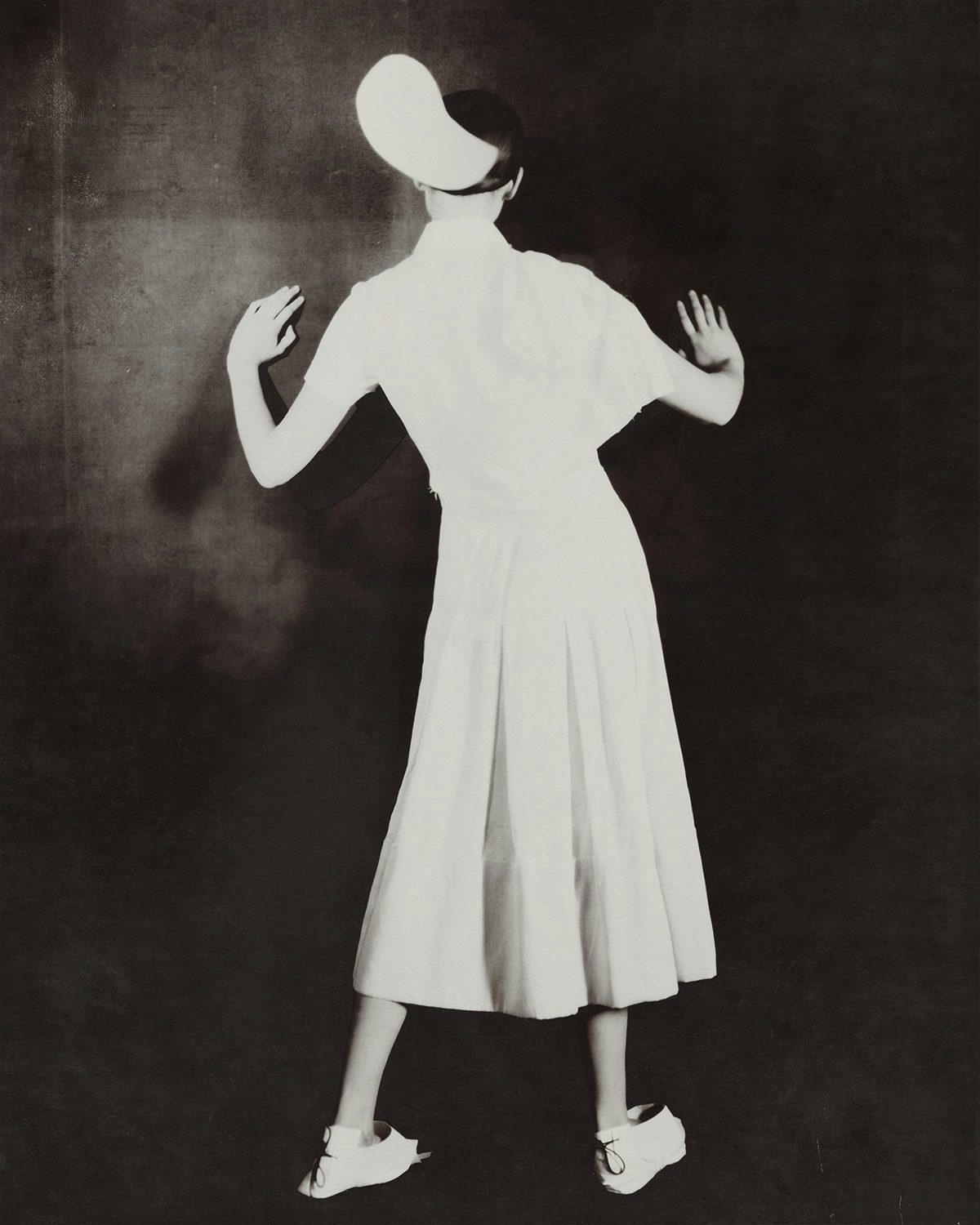

In a lot of ways, Roversi’s photographs are more akin to paintings and, like a painter, he performs unexpected tactile interventions, whether on set or in post production. Set and costume designer Shona Heath recalled the time he rescued a shoot by pulling out small torches, turning the garments into a canvas for a lightshow – a method he has been using since a chance discovery on a Comme des Garçons shoot in the mid-1990s.

Besides his four-decade creative relationship with Comme des Garçons’ Rei Kawakubo, Roversi has also nurtured close collaborations with the creative directors of fashion houses including Yohji Yamamato and Dior, many of which are revisited in detail in the book.

Early on in his career, Roversi worked as a photographer for the Associated Press, but by the mid-1970s he managed to crack the world of fashion image-making, a field similarly dictated by relentless rhythms. Yet he appears to have resisted the industry’s pressurised forces that lead to formulaic work, a feat made possible by his unwavering artistic curiosity.

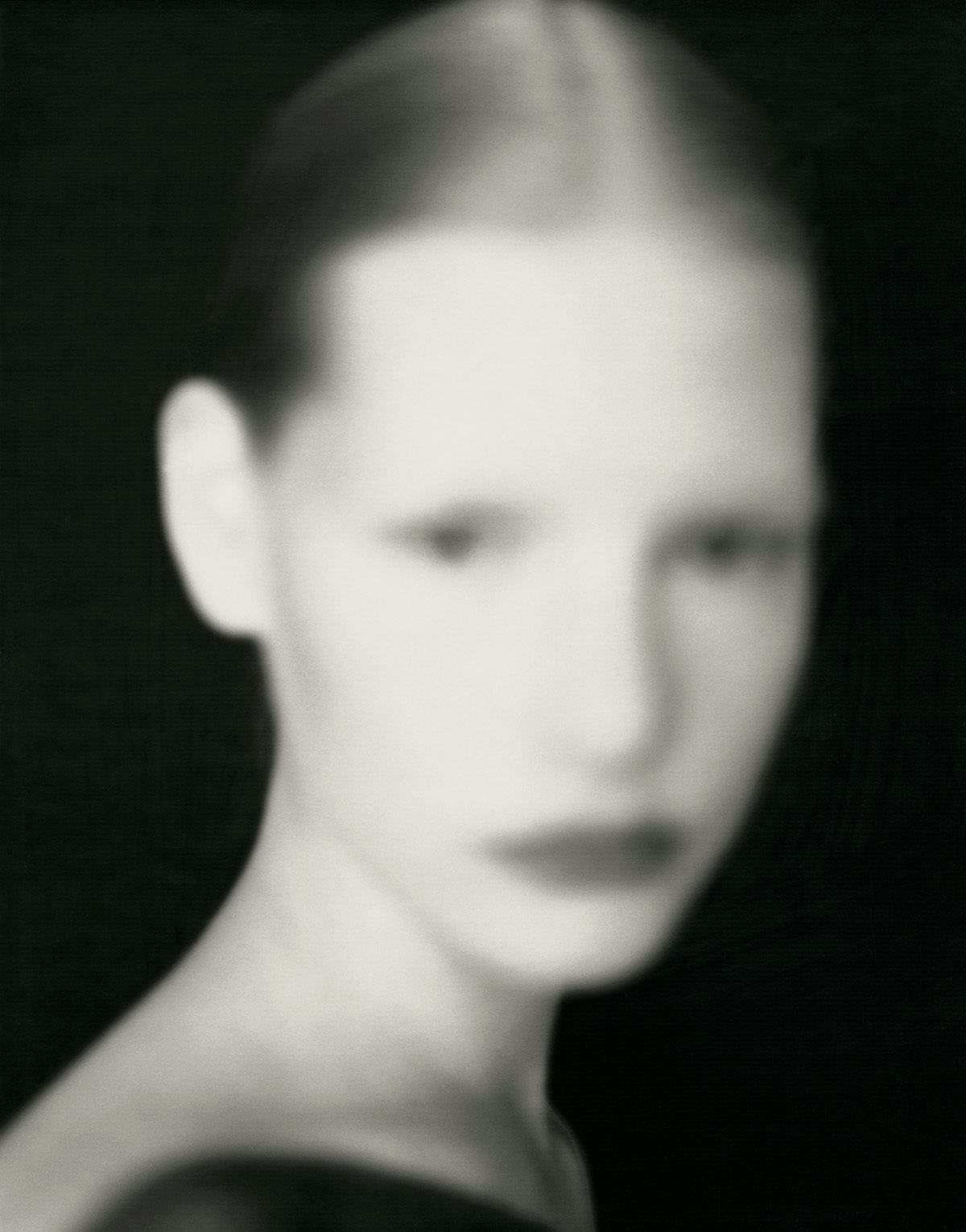

Roversi has long had a special affinity for Polaroid, to the point that he has been known to call it a ‘Paoloroid’. However, he has never been interested in conventional uses, instead introducing Polaroid film stock to the slow, methodical discipline of large format image-making. Andy Warhol was Polaroid’s most famous disciple, and there are echoes of his work – namely his screenprints – in Roversi’s, particularly his photos featuring electric hues, high contrast and distortion.

Yet he is just as adept at delicacy, his gentle images featuring muted tones, soft focus and tarnishes suggestive of an altogether different time. “With its transparent and immaterial nature, the medium of photography seems to be perfectly designed to translate the beauty that Roversi seeks,” Lécallier says of his portraiture, “a beauty that seems to hang in the air, indefinable, ephemeral.”

Paolo Roversi is published by Thames & Hudson; thamesandhudson.com