New Malick Sidibé book shifts the focus to the frame

A new publication showcases the vibrant hand-painted frames that the Malian photographer focused on in the latter part of his career

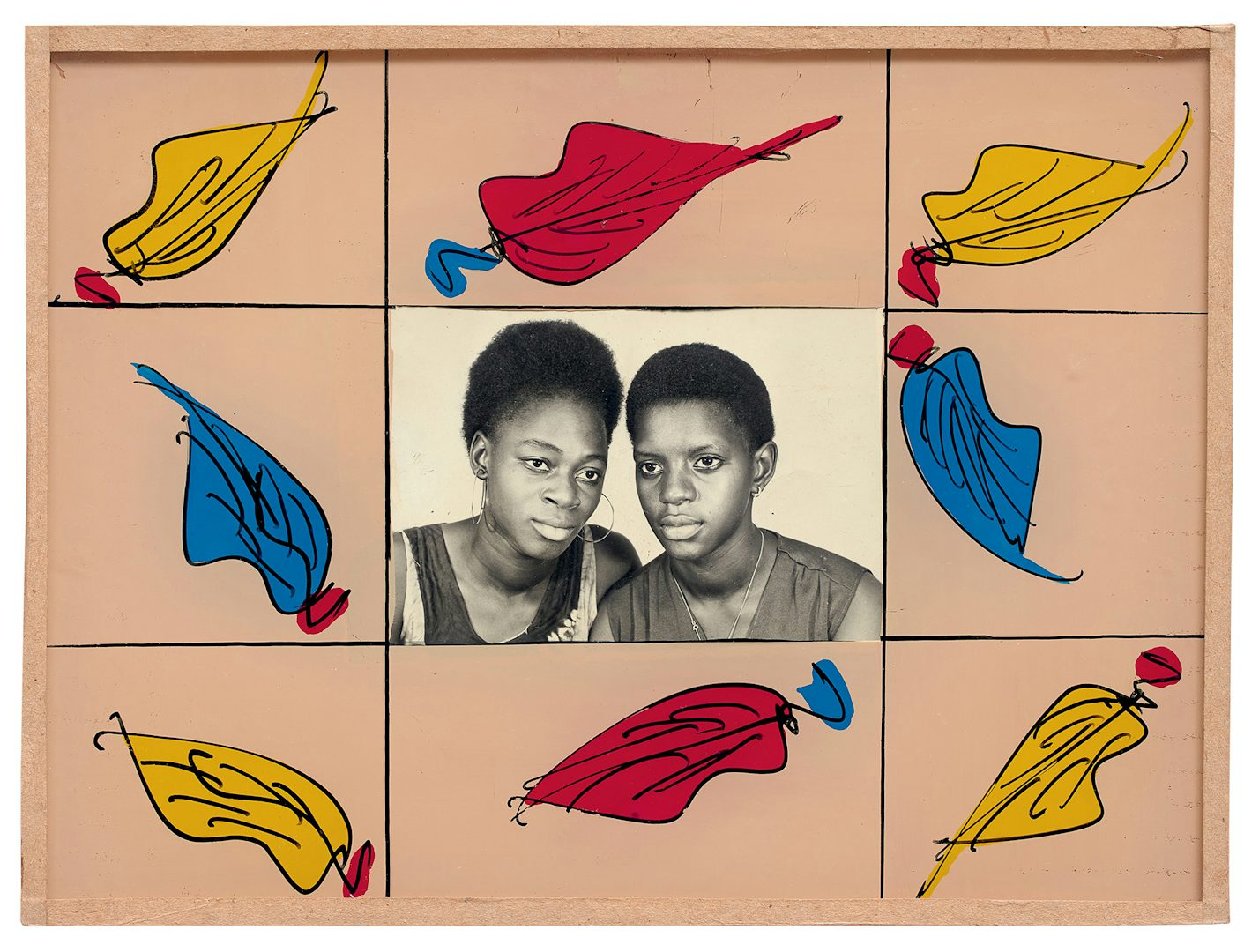

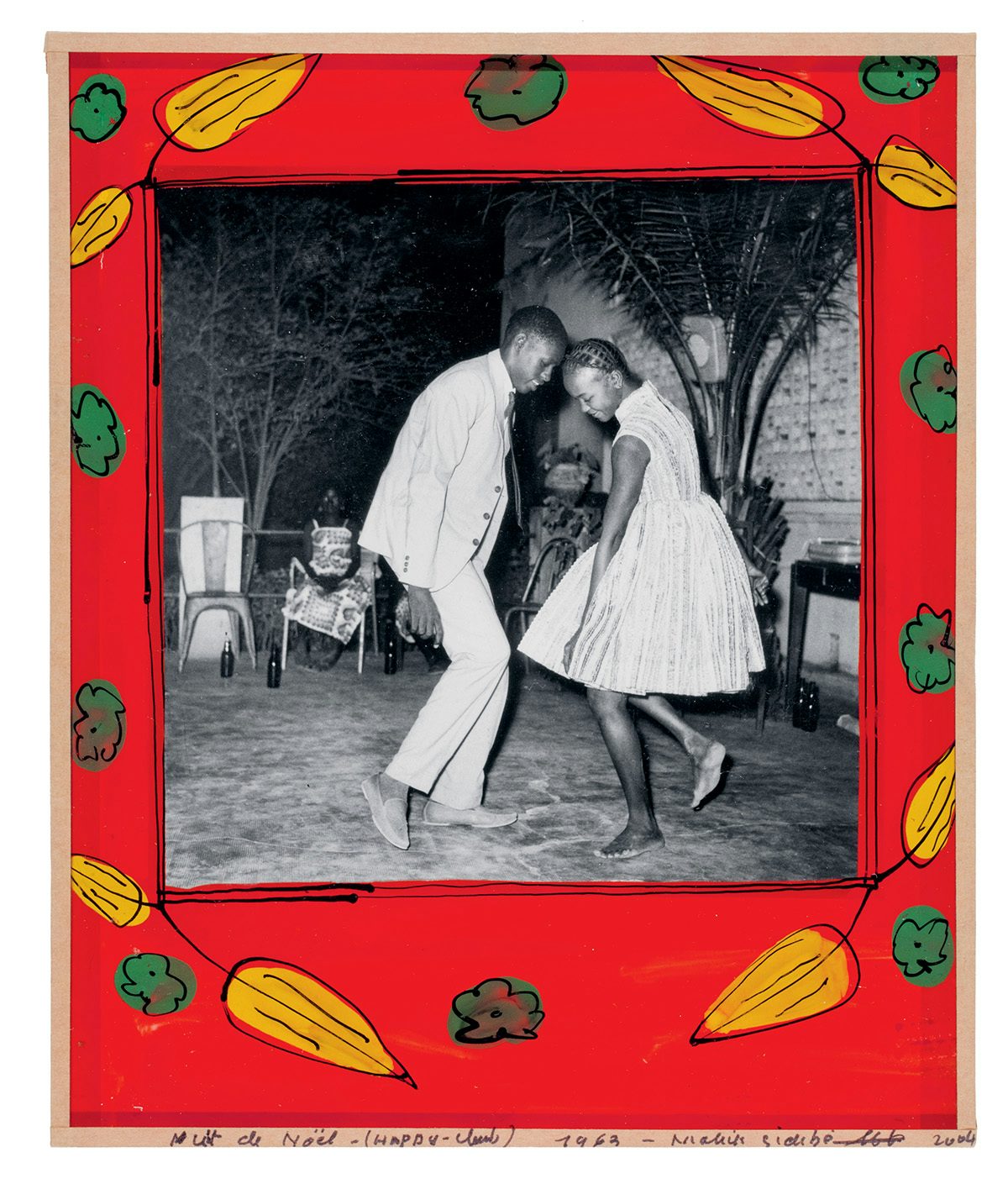

Malick Sidibé’s black and white photographs of a post-independence Mali in bloom have ensured his place as a leading photographer of the 20th century. Alongside his lively photos of young people enjoying nightlife, Sidibé amassed a substantial number of studio portraits from his space in the capital, Bamako, many of them against intricately decorated sets of patterned textile backdrops and rugs.

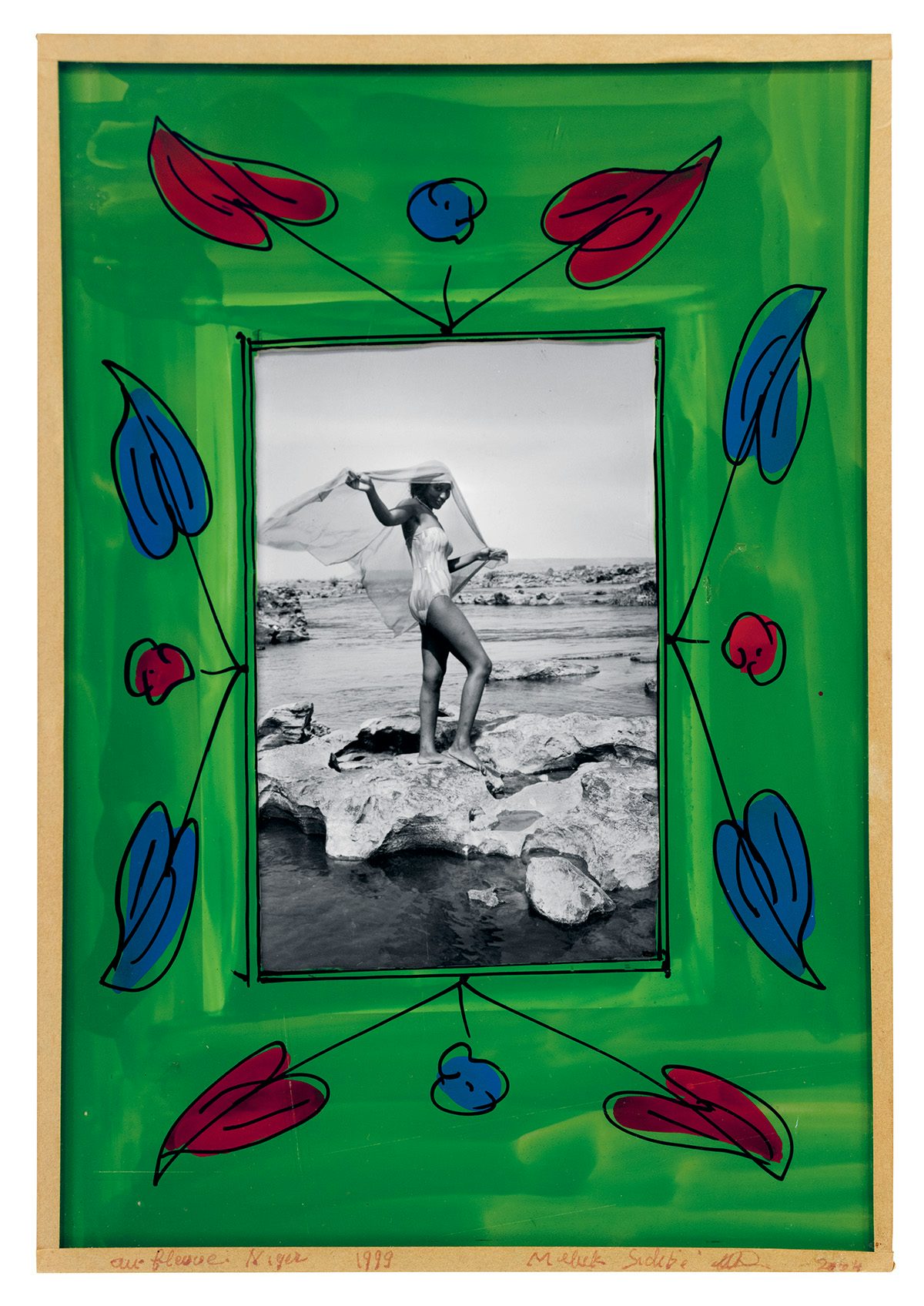

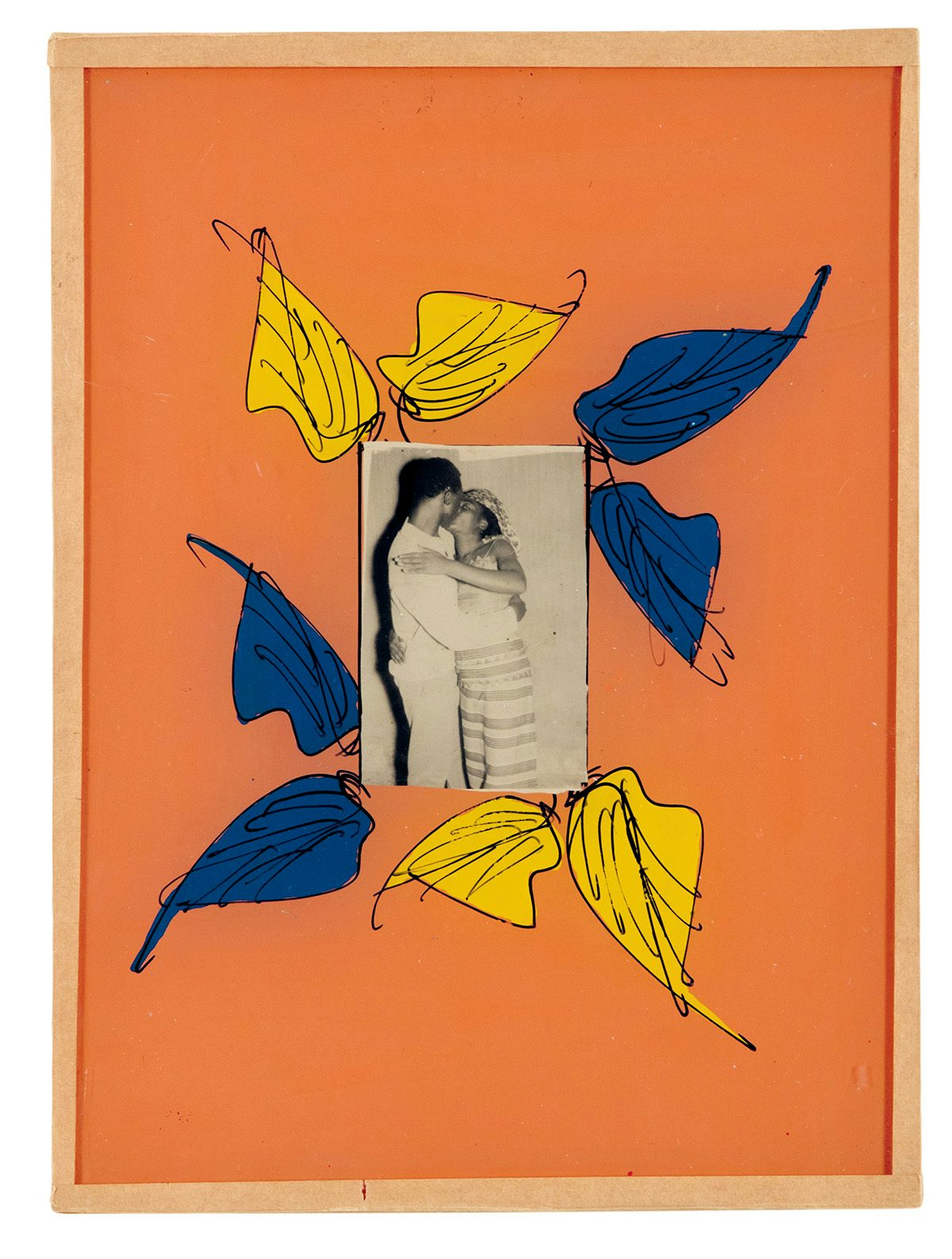

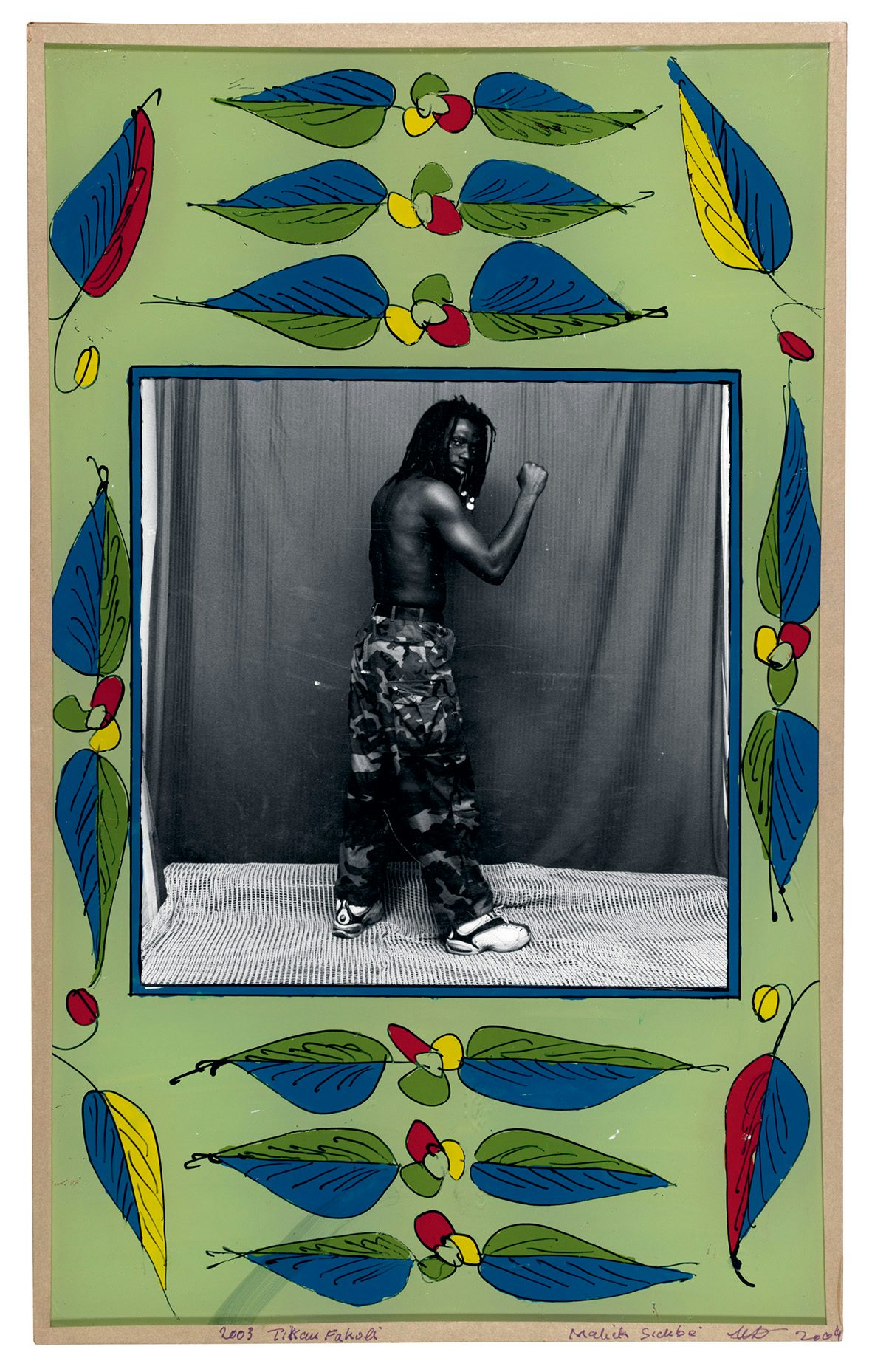

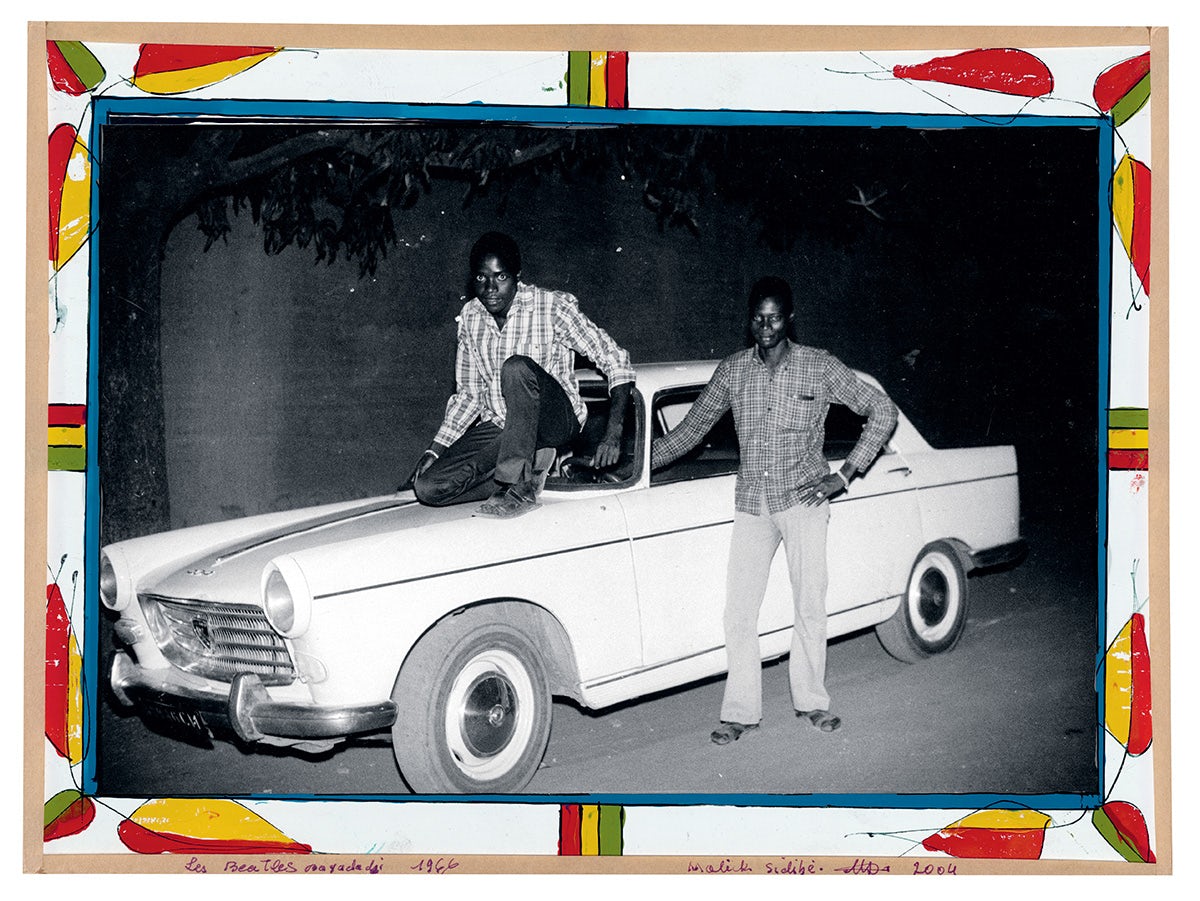

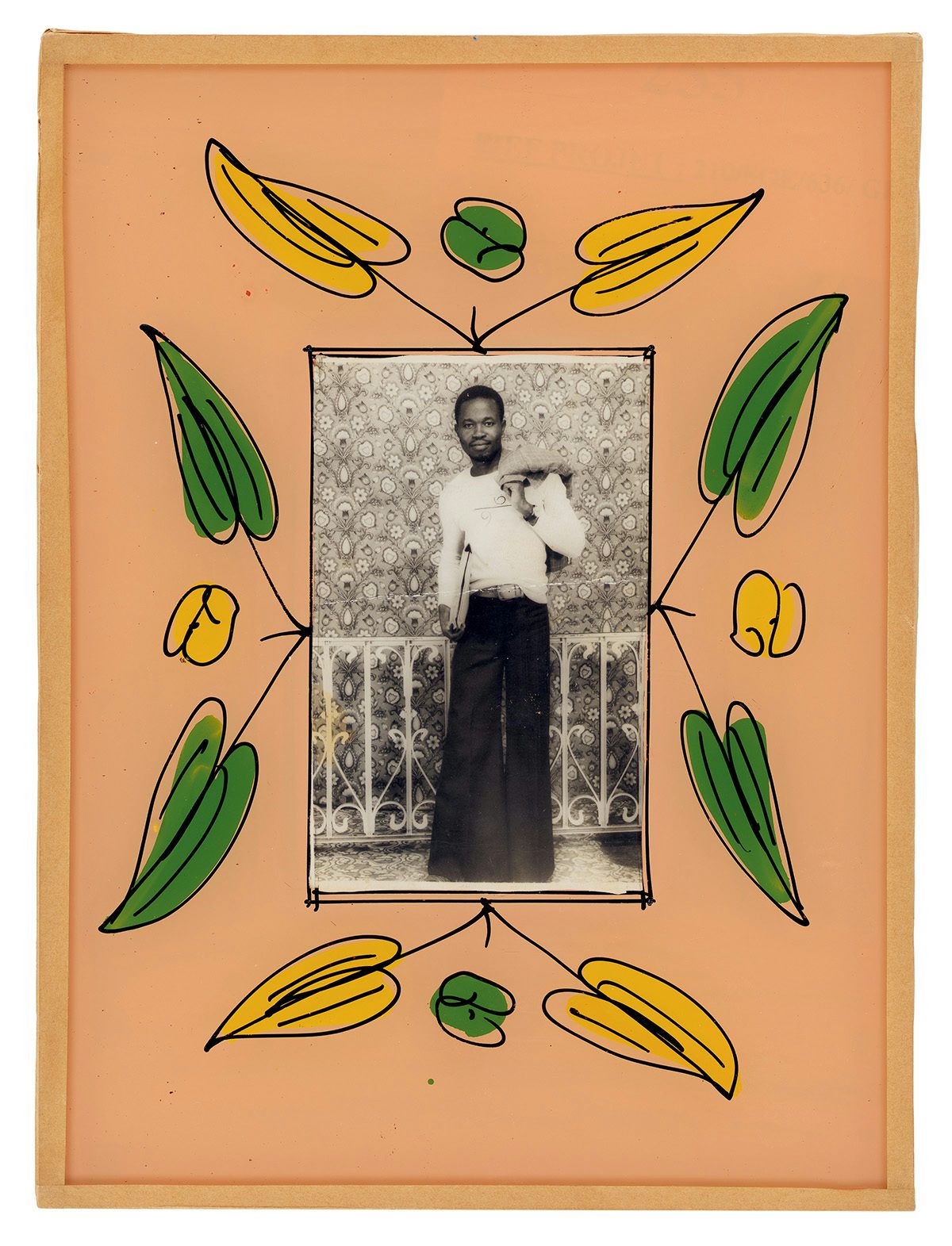

In a new book published by Loose Joints, the graphic details ordinarily embedded in his compositions are lifted out of the camera’s frame and applied to the physical frame itself. Densely saturated glass borders are overlaid with motifs, many the shape of leaves and flowers, loosely daubed in equally bright flashes of colour.

The collection of painted frames came about as a result of a collaboration between Sidibé, artist Cheickna Touré and Touré’s sons, encouraged by the founders of Jack Shainman Gallery in the early 2000s, resuming a partnership between the photographer and Touré that had begun decades earlier.

The frame would perhaps seem like the second-most important element in a photographer’s practice after the image itself. However, the publisher describes the process as “layering painted borders with photographic portraits”, suggesting that they are the foundation rather than an afterthought. “These frames were not mere embellishments but functional objects,” they add.

In the introduction, writer, curator and archivist Amy Sall recalls the arrival of reverse glass painting in Sidibé’s studio as being entangled in histories of migration, colonialism and religion, encompassing practices found in medieval-period Europe and the Middle East, travelling into the African continent via its northernmost countries, perhaps influenced by Muslim pilgrimages along the way.

The practice eventually found its way to Mali, it’s suspected, through Senegal, where using reverse glass paintings as frames was growing in popularity, and with which Mali had been joined briefly to form the Mali Federation under colonial rule in 1959. Touré – who also worked with another significant Malian photographer, Seydou Keïta, as a framer – taught his sons the art of reverse glass painting specifically for the commission; its journey is not just geographical but intergenerational, too.

The book will be discussed at the ICP in New York in a conversation between Sall and the organisation’s creative director, David Campany, on April 19. Also in New York is a concurrent solo exhibition of his broader work at Jack Shainman Gallery called Regardez Moi, which celebrates Sidibé as a chronicler of Bamako’s populations in this era of profound change.

The gallery describes Sidibé’s work as both “a reflector and a loudspeaker” capable of “magnifying” the energy of those he encountered, which is also a fitting way to describe the vibrant frames surrounding his famed images courtesy of Touré’s painted interventions.

Painted Frames by Malick Sidibé is published by Loose Joints; loosejoints.biz